Image Details

Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

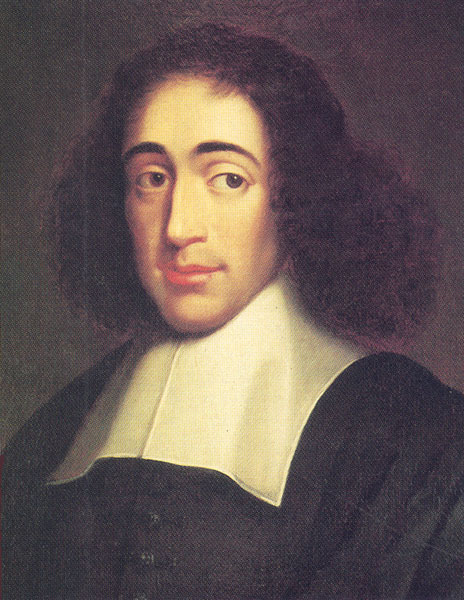

A pair of independent thinkers, Martin Luther (1483–1546) and the Jewish Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza (shown here, 1632–1677) both offended the religious leaders of their day. By confronting the Catholic Church hierarchy, Luther sparked the Protestant Reformation, but Spinoza, in a less historically dramatic way, had his own share of run-ins with the authorities of his religious tradition. Trained in Hebrew and talmudic studies as an Amsterdam youth, Spinoza was eventually excommunicated from the Jewish community because of his freethinking views.

Though very different in temperament, experience and conviction, both men contributed to the development of modern biblical criticism. Protestant leaders like Luther (who produced a German translation of the Bible) wanted to provide all Christians with vernacular translations of scripture, a desire that stimulated the study of biblical languages among Protestant and Catholic scholars alike. Their interest also generated new, more systematic forms of critical analysis, as scholars began to examine the different readings preserved in various manuscripts and translations.

Spinoza (portrayed here in an anonymous 17th-century painting) went even further. Like the reformers, he argued that biblical scholars should have a rigorous knowledge of Hebrew. But he also insisted that scholars needed to develop a history of the biblical text by reconstructing, as far as possible, the context in which the biblical books were written, the original intentions of the authors and the circumstances under which the texts were edited, shaped and transmitted. With this approach, Spinoza laid the methodological groundwork for modern biblical criticism.