Image Details

Photo by Scala/Art Resource, N.Y.

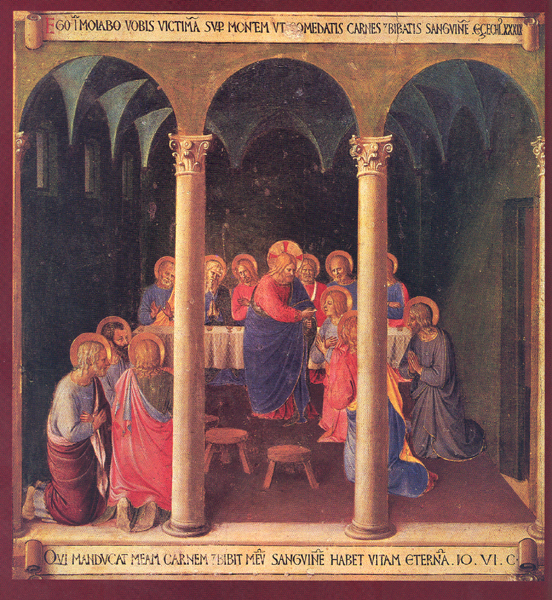

“The Last Supper.” The disciples kneel to receive the Eucharist—bread and wine—from Jesus in this painting by the Italian artist Fra Angelico (1387–1455). A prior of the monastery of San Marco in Florence (“Fra” means brother), Fra Angelico set the New Testament scene in his own realm, amid columns and arches reminiscent of a Renaissance church. For Fra Angelico, Jesus is more like an abbot with his monks than a Galilean rabbi with his disciples.

Jesus’ words at the Last Supper, “This is my blood,” related in the Gospels of Mark, Matthew and Luke, are usually understood to refer Jesus’ own flesh and blood. But in the Jewish world of Jesus, drinking blood—even symbolic blood— would have been considered blasphemous; consuming human blood and flesh was unthinkable. This understanding, argues author Bruce Chilton, developed later, near the end of the first century C.E., as Christianity came under Hellenistic influence.

For Jesus, offering wine and bread symbolically replaced the sacrifices made at the Jerusalem Temple, which he found both impersonal and impure: In his time people no longer brought their own animals to the Temple, but bought them from merchants and, when the priests slaughtered the animals, were less involved than they had been. In the intimate, inclusive setting of the Last Supper, Jesus substituted offerings of wine and bread for the blood and flesh of Temple sacrifices.

In his painting, Fra Angelico links Jesus’ offering with an Old Testament vision. The banner above the scene quotes Ezekiel 39:17, in which God tells the, birds and the beasts that they will consume Israel’s enemies: “I will prepare for you a sacrifice on the mountain so you may eat flesh and drink blood.” The New Testament words “the one who consumes my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life” (John 6:54) appear below. It is typical of the Christianity of Fra Angelico’s period that the impurity of the vision is ignored when used as an image of the Eucharist.